Project Eve, built from the ground up in Canada. Click image to enlarge |

Article and photos by Jil McIntosh

Photo Gallery:

EV 2011 Conference and Trade Show

Nothing to do with vehicles happens in a vacuum, but nowhere is that more evident than with the ongoing interest in electric vehicles. It’s not enough for automakers to simply put battery-powered motors into cars and trucks. There also has to be consideration for infrastructure, charging standardizations, safety, customer acceptance and ongoing technology, especially for their batteries.

All of these issues were part of the EV 2011 Conference and Trade Show, held in Toronto on September 26 to 28, 2011, and presented by Electric Mobility Canada, a national not-for-profit organization dedicated to the promotion of electric vehicles (http://www.emc-mec.ca/). It was primarily a series of conferences for the industry – it was a tough decision, but I turned down the opportunity to sit in on the no-doubt-riveting “Phosphate Coating for 5V Cathode Spinel LiMn1.5 NI0.5 O4” presentation – but on the opening day, media reps were invited to attend and take some gasoline-free test-drives. Alongside the now more familiar models sold by or upcoming from mainstream manufacturers, there was also a Canadian-built prototype and a Chinese-made electric truck.

AGT low-speed electric truck (top), and its interior, with manual transmission. Click image to enlarge |

The big announcement at the conference was “Building Canada’s Green Highway,” a vision for Canadians to travel coast-to-coast using alternative energy to power their vehicles. The idea is to supplement the petroleum stations currently available with vehicle electricity and the accompanying infrastructure for charging. It is modeled on the West Coast Green Highway, a 2,172-km stretch of the I-5 interstate that uses a private-public partnership to focus on the need for alternative transportation methods and their infrastructure. Electric Mobility Canada is promoting the model to various levels of government in the hopes that it will turn into a concrete project.

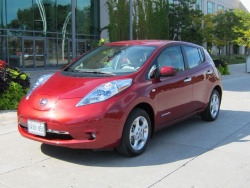

The event took place on the grounds where Toronto’s Canadian National Exhibition is held each summer, in a repurposed building that was originally the Automotive Building for the annual fair. Parked outside were some of the current and future offerings: Smart Fortwo Electric, Chevrolet Volt, Ford Transit Connect Electric, Mitsubishi i-MiEV, Nissan Leaf, and Toyota Prius Plug-In Hybrid (PHEV). There was also Project Eve, a Canadian-built prototype, and a low-speed waste management truck from AGT Cars, a Chinese manufacturer, along with electric vehicle charging stations (EVSE) from Eaton and Schneider Electric.

There are many hurdles to overcome before electric cars go mass-market (if, in fact, they ever do). The car itself isn’t the difficulty; automakers nailed electric vehicles back in the late 19th century. In fact, electric cars were initially more popular than gasoline ones, at least until Cadillac invented a self-starter that eliminated the oft-difficult and dangerous job of cranking over a gas engine to start it. The major issue today is the battery, which hasn’t kept pace. Simply put, the more range a battery has, the more expensive, larger and heavier it is. Companies are working on newer, denser materials to squeeze more energy into smaller batteries, but it’s still a challenge.

Mitsubishi i-MiEV (top); The fully-electric Ford Transit Connect; Smart Fortwo Electric Drive; Nissan Leaf; Chevrolet Volt. Click image to enlarge |

The other problem is the infrastructure necessary to keep those batteries charged. Initially it’s expected that electric vehicles will go to people who can easily charge them at home or at work, which will probably rule out condo dwellers until charging stations are installed. But along with making charging stations as common as gasoline stations, standardization is an essential part of electric acceptability. “The receptacle on the car for charging is an SAE standard, that’s established,” said Ian Forsyth, director of corporate planning for Nissan Canada. “But the vehicle supply equipment, the interface between the car and the grid – those standards are not resolved. The cord, temperature resistance, the amperage rating of the unit itself, the waterproofness, other overload issues and all of those things are part of it.” CSA, the lead body for certification in Canada, is working on the standards but they are not yet complete, he said.

Forsyth said that we’re luckier in North America, since our electrical plugs are the same. “The problem in Europe is more severe because almost every country has a completely different way of connecting to the grid. Their plugs are different from country to country. Standardization not only deals with the car end of it, but the grid end, whereas in North America that’s not a problem because plugs are standardized. Every charging station will charge every electric vehicle in Canada. They ‘talk’ to the car and the car ‘talks’ to the EVSE. “Yes, I’m plugged into a battery, do I detect any fault? No, okay, let the power flow.”

Electric vehicles also present new challenges for automakers because, in many cases, it’s the first time they’ve had to concern themselves with refueling infrastructure. When they build a gasoline vehicle, they just ship it out to the dealer for sale. It’s up to the gasoline companies to find oil, refine it into fuel, and get it to the gas station. With alternative vehicles, the automakers have to play an integral role in the big picture. “We’ve been working on gas for many years and we know all the ins and outs,” said John Viera, director of sustainability for Ford Motor Company. “We don’t have all the battery information, so we do a lot of partnerships. We partner with universities, other companies in some cases, other businesses, trying to partner with other entities that could help advance technology faster, and that’s particularly relevant to electric vehicles.

“With gasoline, we never had to worry about how the customers get their fuel,” Viera said. “The good news is that everyone has electricity at their house or work, so we’ve decided to work on how we provide charging equipment that is easily installable in people’s homes or at work. We think the majority of charging will happen with people charging at home or work.”

Electric vehicles may not burn gasoline, but they’re definitely not self-sustaining, and the industry faces several new challenges including finite resources such as lithium, the method by which the electricity is produced, the effect of large-scale charging on the power grid, and battery recycling. “We’re working with other automakers on the whole recycling process,” Viera said. “We’re not there yet, but we need to get together as an industry to address that issue. What’s the protocol for removing the battery, where are they transported, where do they go? This is not a competitive advantage. This is something we’re all going to need.”